|

Today pepper is our single most

commonly used spice, routinely

offered in fine restaurants and

fast food joints alike and

universally available in stores

and supermarkets. It is

therefore hard to imagine just

how highly prized pepper was in

ancient and medieval times and

how it spurred a complex trade

that saw peppercorns travel

distances so enormous that their

origins remained obscure even to

their purveyors. Along the way,

fortunes were made, lives were

lost, and the spice became

enriched with its connotations

of mystery and exoticism

|

HERMAN MOLL (1736) |

|

Since at least the first

millennium BC, pepper was

regarded as an ultimate luxury,

inessential to survival yet

highly desired for ritual,

medicinal and culinary purposes.

The origins of this desire

stretch back to ancient Egypt,

with the great pharaoh Ramses II

being the first known consumer,

albeit posthumously: peppercorns

were found in the nostrils of

his mummified corpse. In ancient

Greece, pepper was used

medicinally and the Chinese have

used it in their cooking since

at least the fourth century. The

Romans' conquest of Egypt gave

them regular access to pepper,

and it became a symbol of

luxurious cookery. It was traded

ounce for ounce with precious

metals: When Rome was besieged

in the fifth century, the city

allegedly paid its ransom in

peppercorns, and the spice

remained an accepted form of

"currency" throughout the Middle

Ages.

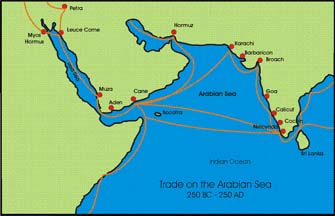

The period from roughly the

first century BC to the first

century of our era witnessed a

surge in the pepper trade as

navigators began to understand

the pattern of the Indian Ocean

monsoon, and the surge resulted

in more detailed knowledge about

the lands where the pepper

grows.

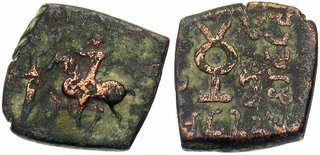

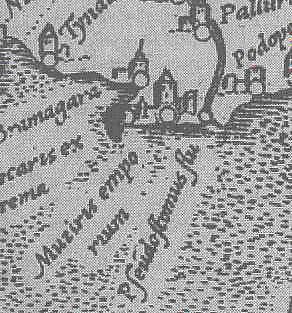

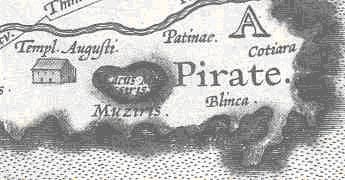

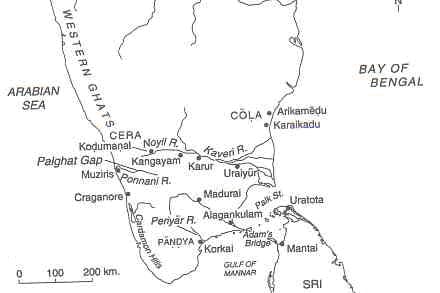

In 70 AD, the Periplus Maris

Erythraei, an anonymous

merchant's guide to the Red Sea,

recorded information on the

spice trade and the now lost

Indian port of Muziris. Large

ships are sent there, the author

reports, "on account of the

great quantity and bulk of

pepper" that is only grown in

that region. Even though

archeologists still debate its

exact location, it is clear from

the Periplus and other

references that Muziris was

located near the modern city of

Kodungallor (formerly known as

Cranganore, its colonial name)

on India's Malabar Coast, where

black pepper is native.

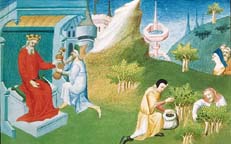

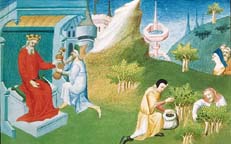

Pepper was once a gift fit for

kings; above, a French

manuscript illustration from the

early 15th century shows both

harvesting and royal

presentation.

|

|

The Malabar Coast comprises a

narrow sliver of land on the

southwestern tip of peninsular

India, hemmed in by the Arabian

Sea to the west and the mountain

range of the Western Ghats in

the east. This region, now

largely contained in the

northern part of the Indian

state of Kerala, is located in

the humid equatorial tropics:

the annual monsoon rains nourish

the fertile soil, feed the

extensive network of backwater

canals, and support the region's

rich biodiversity. In addition

to being the source of pepper,

Malabar's position at the center

of the Indian Ocean made it a

natural location for commerce

and transshipping. For these

reasons, foreign merchants

hailing from the different

corners of the Indian Ocean

trading world established

settlements in Malabar's ports

and brought with them not only

their commercial expertise but

also their cultures and creeds. |

BIBLIOTHEQUE NATIONALE /

BRIDGEMAN ART LIBRARY |

|

As

the original suppliers of pepper

to the Mediterranean world, the

Persians had sailed along the

coast to Malabar since the

earliest days of maritime

navigation. Jews are believed to

have arrived and established

synagogues as early as the sixth

century BC. The Christians of

modern Kerala trace their

ancestry to Thomas the Apostle,

who they believe came to Muziris

in the year 52; they are known

to this day as St. Thomas

Christians.

|

|

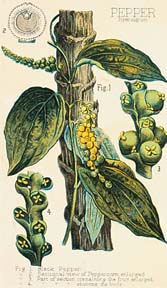

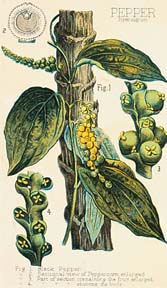

Peppercorns are the dried fruit

of the wild climbing vine Piper

nigrum, which is native to the

rich soil and humid climate of

the Malabar Coast. It is

unrelated to the American chili

fruit, often called "chili

pepper."

In the same century, ships from

China reached South India and

created the long-lasting

connection between the Chinese

empire and Malabar: This was as

evident to medieval visitors,

who spoke of Malabari

communities known as "sons of

the Chinese," as it is to modern

tourists who marvel at the

peculiar shore-based fishing

contraptions known as "Chinese

nets." Traders from other parts

of India, especially Gujarat to

the north and Coromandel on the

east coast, also established

permanent trading communities on

the Malabar Coast, often

specializing in particular

goods. But what would prove to

be the most profound foreign

influence on Malabar did not

arrive for another five

centuries, when a new religion

spread across the lands around

the Indian Ocean, galvanized

their commerce and created

immense wealth through the trade

in pepper. |

CYNTHIA HART DESIGNER /

CORBIS |

|

Despite their reputation as a

desert people, Arabs had long

been involved in maritime trade.

Yet it was only with the

unifying, expansionist and

proselytizing energy of early

Islam that Arabs were able to

develop their traditional

dominance over the caravan and

Red Sea trade into a network of

Muslim settlements that rapidly

spread along the Indian Ocean

littoral. Under the early

caliphates, this Islamic network

matured to encompass most of the

Indian Ocean world from East

Africa to the southern coast of

China. It carried with it not

only the beliefs of Islam but

also the Arabic language,

shari'a courts able to enforce

common legal standards and

shared commercial practices that

favored the interaction of these

settlements. Merchants residing

in foreign ports were able to

learn the local language,

establish and maintain business

contacts, and act as

cross-cultural brokers. Muslim

trade settlements developed into

particularly effective

organizations because of the

political unity initially

created by a burgeoning Islam,

the great emphasis on literacy

within its culture and the

practice of pilgrimage, which

kept its heartlands in

communication with even the most

far-flung settlements. Even

though the bulk of Indian Ocean

commerce was carried on Indian

and Chinese ships, and despite

the continued significance of

Jewish merchants, Arab Muslims

increasingly dominated trade in

its most profitable commodity:

pepper. |

|

|

|

|

The

Piper nigrum vine grows readily

and widely, and it reaches

several meters in height. Like

Indian Ocean navigation, the

rhythm of growing and harvesting

is set by the monsoon. Black,

white and green pepper are all

fruits of the same plant,

respectively dried, decorticated

and brined or freeze-dried.

Air-drying black pepper requires

frequent turning, and is still

most often accomplished simply

by spreading the pepper out in

the sun.

The momentous commercial

expansion during the early

centuries of Islam was driven by

the demand for spices in Europe

and in the grand capitals of the

new Islamic states. Within the

lucrative spice trade, pepper

was the most important commodity

in bulk and value, and so the

Malabar Coast remained of

central importance to the Indian

Ocean trading world. In his

description of Malabar, the

14-century Moroccan traveler Ibn

Battuta recorded his

astonishment at seeing pepper,

elsewhere valued by the grain,

"being poured out for measuring

by the bushel, like millet in

our country." It is therefore

not surprising that Malabar was

the first region of India to

attract Muslim traders in

significant numbers. The Malabar

Coast was originally inhabited

by the Dravidian people, who

were distinct in their languages

and culture from the Indo-Aryans

of northern India. Organized

religions came to Kerala in the

form of Jainism, Buddhism and

later Hinduism, and expressed

themselves in the construction

of temples—their profusion in

the region has led Kerala to be

called "the land of temples." A

revived Hinduism developed into

the region's predominant

religion from about the ninth

century onward, when Kerala's

royal houses patronized Brahmins

from North India.

The origins of Islam on the

Malabar Coast began, according

to legend, with the last king of

the South Indian Chera dynasty,

which had ruled Malabar since

the beginning of its recorded

history. Cheraman Perumal, the

tale goes, converted to Islam

after having dreamt of a

splitting moon and then meeting

Arab pilgrims who reported that

the Qur'an mentions just such a

miracle (54:1–2). The king

resolved to join the pilgrims in

their journey to Makkah, but not

before dividing his kingdom

among his princes, a

fragmentation that would

characterize the region for many

centuries.

Having fallen ill on the return

journey and unable to make it to

his homeland, the king entrusted

the same pilgrims with the

mission of founding mosques and

propagating his new faith in

Kerala. Many of the oldest

mosques in the region are said

to have been founded by these

pilgrims, who were dispatched

all along the coast to serve as

qadis to its fledgling Muslim

communities.

The legend of Cheraman Perumal

is similar to conversion myths

in other parts of Asia and

appears to be a confusion of two

distinct traditions, one

relating the end of unified

Chera rule over Kerala and the

other the conversion of a king.

Its appeal and longevity,

however, are testament to the

exceptional circumstances that

surrounded the introduction of

Islam to Kerala and to the

unique history of the

communities it created.

Furthermore, many aspects of

this tale can be linked to

historical truths. To begin to

understand this blend of fact

and fiction, therefore, we must

look at the intriguing history

of the Muslims of Malabar and

their unique blend of Islamic

traditions and South Indian

customs.

Islam was introduced to the

Malabar Coast peacefully by Arab

traders in search of pepper and

by Sufis who traveled within the

commercial networks. To this

day, most Muslims of Malabar

adhere to the Shafi'i school of

Islamic law, which was dominant

among Muslim merchants across

the Indian Ocean world. They are

also more closely linked to Arab

culture than to the Persian

influence that was brought to

the rest of India by invaders

from the north. Muslim merchants

settling in Malabar ports

married (often multiple) local

women. Their offspring were the

first generation of Indian-born

Muslims, and their upbringing in

both Arabic and the local

language, Malayalam (not related

to the Malay language of

Southeast Asia), was an

excellent preparation for future

work as brokers. In this manner,

the ports of the Malabar Coast

became ever more closely woven

into the network of Islamic

trade spanning the Indian Ocean,

and the wealth of the expatriate

merchants and their associates

increased.

As the legend of Cheraman

Perumal already suggests,

another significant factor in

the introduction of Islam to

Malabar was conversion. Aside

from rare exceptions, these did

not, however, occur in the

ruling class but in the lower

strata of society. Hinduism in

this part of South India had

developed a particularly rigid

system of caste division, with

social intercourse between

castes severely restricted to

avoid ritual pollution.

Conversion to Islam was

therefore a chance for low-caste

Hindus to break free of such

limitations, and also opened new

opportunities for economic

interaction with the prosperous

Arab merchants. This group of

new Muslims native to Malabar

developed into a distinct

community known as Mappilas (or

Moplahs). These new converts

preserved many of their

traditional practices and

integrated them into their new

Islamic identity. Some Mappilas,

for instance, continued the

practice of matrilineality in

which descent is understood to

be of the mother's bloodline.

The particular cultural heritage

of this community is preserved

in the Mappila songs, an

indigenous form of devotional

folklore in the Malayalam

language.

From about the thirteenth

century onwards, Kozhikode

(anglicized "Calicut") emerged

as the coast's dominant port. It

was the center of a princely

state ruled by hereditary

sovereigns known as Zamorins.

These were particularly renowned

for their tolerance on the one

hand—they for instance granted

merchant communities independent

jurisdiction over their

members—and their scrupulousness

in upholding property rights on

the other, and they built a

reputation for honesty that

helped to turn Kozhikode into

the region's principal port. Ibn

Battuta explicitly states that,

because of this reputation,

Kozhikode had become "a

flourishing and much frequented

city" and one of the most

important ports in the world.

Foremost among its cosmopolitan

assemblage of foreign merchants

were the Muslim traders. These

became over time not only the

Zamorins' main source of tax

revenue but also allies in their

ambitions to subjugate other

princely states, often through

the provision of ships and

sailors for naval warfare.

Historians such as K. M.

Panikkar are of the opinion that

the Zamorins were on course

towards subjecting and unifying

Malabar under their rule, but

that "this very process gave

rise to jealousies and feuds"

that were easily exploited by

the Portuguese after their

arrival on the coast. |

|

Pepper

Pliny, writing his Natural

History in the first century,

was puzzled by the demand for

pepper that dictated its high

price: "Its fruit or berry are

neither acceptable to the tongue

nor delectable to the eye: and

yet for the biting pungency it

has, we are pleased with it and

must have it set forth from as

far as India." By Pliny's time,

pepper had long been part of

European commerce and

imagination about the East.

Alexander the Great is believed

to have brought pepper back from

his expeditions. He introduced

its Sanskrit name, pippali, from

which the Greek piperi was

derived and passed on to the

Semitic languages (Hebrew pilpel

and Arabic filfil) as well as to

the European languages through

the Latin piper.

Today pepper is still considered

the "king of spices" and added

to almost any kind of recipe.

Pepper was already the most

frequently used oriental spice

in medieval Europe, and

descriptions of lavish banquets

often refer to the luxuriously

large quantities of pepper used

in their preparation. Aside from

its culinary function of spicing

up foods, pepper was also valued

for its supposed medicinal

properties, in particular as an

antidote to poisoning and as a

cure for impotency. Its high

price relative to volume also

made it a useful currency: The

Roman emperors stored great

amounts of it in their treasury.

As information about the East

increased in late antiquity, so

did the knowledge about the

plants and regions that produced

this most sought-after

commodity.

Peppercorns are the dried fruit

of the wild climbing vine Piper

nigrum, which is native to

Kerala. The vine grows readily

and widely in the rich soil and

humid climate of southern India

and reaches several meters in

height by climbing trees or

trellises. Medieval travellers

to Malabar were amazed at how

widely the pepper vine was

cultivated, with even the

smallest gardens including at

least a few plants. Black, white

and green pepper are all fruits

of Piper nigrum. The peppercorns

are usually picked unripe. If

they are then brined or

freeze-dried, they remain green

and keep a fresh, vegetal flavor

and a mild tang. If they are

sun-dried, the flesh of the

fruit blackens and shrivels to a

thin coating and the spice

develops a richer flavor as well

as more heat. To produce white

pepper, with heat but little

flavor, the peppercorns are

soaked in water and the flesh is

then rubbed off the seeds.

Rarely, peppercorns may be

allowed to ripen to red before

being picked. The name "pepper"

has been profitably applied to

many other plants—Malaguetta

pepper, long pepper and all the

New World capsicums (chili

peppers)—but true pepper is only

Piper nigrum, and the

connoisseur's choice is Malabar

pepper, preferably the

deep-flavored grade the trade

calls Tellicherry Extra Bold.

|

|

Pepper's high profits helped

propel European colonialism, and

this engraving depicts the port

of Bombay (now Mumbai) in the

mid-18th century, when much of

Malabar's pepper exports passed

through that entrepôt into the

holds of ships of the British

East India Company.

When Vasco da Gama's fleet

reached Kozhikode in May 1498,

he came "in search of Christians

and spices." He was initially

content to imagine having found

the former: He believed the

Hindus to be an aberrant

Christian sect and even offered

prayers at a Hindu temple,

albeit somewhat puzzled by the

|

|

|

depiction of "Our Lady" with

multiple arms. The desire for a

monopoly of the pepper trade,

however, was more difficult to

quench: The Portuguese soon

realized the prominence of Arab

traders in the town and their

control over the pepper trade.

Laden with a profound antagonism

toward Muslims born of the

Reconquista, the Portuguese were

not content to trade alongside

other merchant communities. When

the second fleet reached Malabar

in 1500, its commander, Cabral,

demanded that the Zamorin expel

all Muslim merchants from the

port. This stood in marked

contrast to the long tradition

of free trade that had been the

source of Kozhikode's

prosperity, and the ruler

responded (in the words of the

Portuguese chronicler) that he

could not comply "for it was

unthinkable that he expel 4000

households of them, who lived in

Calicut as natives, not

foreigners, and who had

contributed great profits to his

Kingdom."

Already

during the second European

expedition to India,

confrontation became inevitable:

While the Europeans were no

match for the economic strength

of Muslim merchants, their

ship-mounted artillery and

military expertise proved to be

the force majeure. The

Portuguese seized and destroyed

Muslim merchant vessels,

regularly bombarded Kozhikode

and other ports, and exploited

rivalries among the coast's

princely states to establish

fortified factories.

They used their advantage in

maritime violence to enforce a

royal monopoly on the spice

trade and to sell permits to

other ships that wished to trade

on the coast, and the Portuguese

"pepper empire" was born.

The initial returns on the

expeditions were staggering, and

Lisbon soon replaced Venice as

the main importer of pepper to

Europe. But the Portuguese

violence in India also

galvanized resistance. The

Zamorins together with the

Muslim merchants repeatedly

assembled fleets, but despite

some small victories they could

not break the Portuguese

domination of the sea. The ruler

of Kochi (formerly Cochin) to

the south of Kozhikode, who had

long been a resentful subject of

the Zamorins, allowed the

Portuguese to build a factory as

their base on the Malabar Coast.

A long period of warfare at sea

and on land ensued, and repeated

attempts were made to incite

other Islamic states to assist

the Mappilas' struggle. Egyptian

merchants were able to rouse the

Mamluk sultan to send a fleet,

but after inconclusive

engagements his ships retreated.

As Portugal's power in the

Indian Ocean expanded over the

following decades, Malabar

developed into a major test case

of their imperial ambitions.

Foreign Muslims were able to

move to safer ports and conduct

their business from there. That

they did so successfully is

evident by the great quantities

of pepper that again became

available in the markets of

Alexandria and Venice by the

mid-16th century, often

undercutting the prices at which

the Portuguese could sell it at

Lisbon. The local Mappila

Muslims, on the other hand, had

no choice but to stay and to

resist or evade the Portuguese

monopoly system.

Excluded from the opportunities

of regular commerce, the Mappila

communities became increasingly

militarized. While some resorted

to smuggling and indiscriminate

piracy, others turned to forms

of guerrilla warfare to harass

Portuguese shipping. The

Portuguese, claiming ownership

of all of the sea, soon

described all Mappilas as

pirates and treated them as

such. The Mappilas used small

ports in northern Malabar as

bases, and by the mid-16th

century a Muslim called Kunjali

Marakkar was granted the

hereditary admiralty of the

Zamorin's fleet. He and his

successors inflicted several

defeats on Portuguese armadas,

but when, toward the end of the

century, Kunjali iv asserted his

independence of the Zamorin, the

ruler allied with the Portuguese

and together they eventually

defeated the Mappila

strongholds.

Around the same time, the Muslim

historian Zain al-Din, whose

family had come to Malabar from

Yemen in the 15th century, wrote

his famous Tuhfat al-Mujahidin

(Gift to the Holy Warriors)

describing the cruelty of the

"Franks" in an attempt to

persuade the Muslim states of

northern India to assist the

Mappilas in their struggle. The

historian Stephen Dale argues

that the Mappila Muslims

developed a particular idiom of

holy warfare that, instead of

reflecting the conquest of new

territories by Muslim powers,

expressed a religious struggle

born of individual desperation.

This found expression in popular

festivals (the nerccas), at

which folk ballads celebrating

the Mappila victims of the

anti-colonial struggle are

recited.

The profits of the pepper trade

eventually motivated other

European powers to join the

fray, and in time the Portuguese

were eclipsed first by the Dutch

and later by the British.

Throughout the centuries,

economic and political

circumstances continued to

conspire against the Mappilas

and led to recurrent riots and

attacks. However, the Mappilas

also preserved their link to the

sea, mostly as fishermen in

Kerala's rich waters, and

strengthened their involvement

in riverine trade and

agriculture. Today, Muslims

constitute about a quarter of

Kerala's population and remain

concentrated in the north of the

state on the historic Malabar

Coast; in contrast to other

regions of India, Kerala

experiences very little of the

problems of sectarianism. In

recent years, many Mappilas have

found work in the Middle East,

particularly in Saudi Arabia and

the United Arab Emirates, and so

continue the long-standing ties

that bind the regions and

societies. While historically

pepper may have been as much of

a blight as a blessing for the

Malabar Coast, there can be no

doubt that, because of it, the

region served as a nexus where

the dynamics of world history

were played out —a point for

reflection on the next turn of

the pepper mill. |

|

High roofs and slatted

clerestories helped traditional

Mappila mosques, such as this

one photographed in 1936 in

Ponnani, maintain comfort for

worshipers in the hot coastal

climate. |

BASEL MISSION PICTURE ARCHIVE |

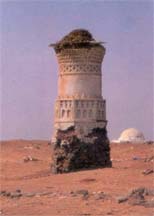

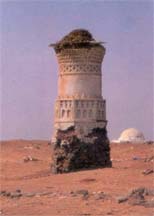

The Nakhuda Mithqal Mosque (or

Mithqalpalli) in Kozhikode is

named for a 14th-century Arab

merchant and dates to 1578, when

it was rebuilt following

destruction of the original by

the Portuguese.

|

SEBASTIAN

PRANGE |

|

Malabar Mosques

Kerala is known as "the land of

temples" for its multitude of

Hindu places of worship, but its

little-known mosques are no less

fascinating in their style and

history. The Malabar Coast is

believed to have been the site

of the first mosques on the

Indian subcontinent, but because

of the destruction brought by

Portuguese bombardments and

subsequent invasions, there are

no mosques that date before the

12th century. The earliest

extant mosques are located in

the old Muslim quarters of

Kozhikode and Kochi and bear

inscriptions noting donations

from Arab merchants and

shipmasters. These traditional

mosques (palli in the local

language, Malayalam) are

remarkably different from the

styles of Islamic architecture

found in Arabia or elsewhere in

India: For example, they do not

feature domes or minarets.

Rather, they show clear

similarities to the design of

vernacular houses and local

Hindu temples. This is partly a

result of the region's

particular conditions (for

instance, the steeply sloped

roofs to cope with the large

amounts of rainfall) and the

available materials and skills.

Yet the similarities were not

only dictated by necessity but

may also reflect the desire to

find a place in the prevailing

ritual landscape: New converts

to Islam would have already had

clear ideas about what

constitutes a sacred space from

the region's existing temples.

The archetypal Malabar mosque is

a covered structure on a

rectangular ground plan, often

with verandas running around the

prayer hall. Especially

characteristic is the intriguing

tiered roof structure, sometimes

covered with copper sheets, with

the upper stories often used as

a madrasa and as offices for the

imam. Mehrdad Shokoohy, a

historian and architect, has

recently studied the mosques of

Malabar and describes in detail

the amalgamation of local

designs with specific features

from the Arabian lands and

Southeast Asia. In this view,

Malabar's mosques are a fitting

manifestation of the remarkable

extent of the medieval Muslim

trading world and its spirit of

cross-cultural stimulation and

exchange

|

|

|

|

|

Left:

A mosque in

an

unrecorded

location,

circa 1939.

Right:

A mosque

near

Chirakkal,

circa 1855.

|

|

|

|

By

Sebastian R. Prange

Acknowledgement: This article

appeared on pages 10-17 of the

January/February 2008 print

edition of Saudi Aramco World.

Refer the book Kodungallur

Cradle of Christianity in India,

by Prof. George Menachery (1987)

at www.indianchristianity.com.on

BOOKS page. Also article "Roads

to India" by Maggy G. Menachery,

in the St. Tomas Christian

Encyclopaedia of india, 1973,

Ed. Prof. George Menachery.

|

|

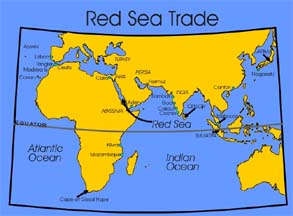

Rome-India Sea Route rivaled

Silk Road |

|

Spices, gems and other exotic

cargo excavated from an ancient

port on Egypt's Red Sea show

that the sea trade 2,000 years

ago between the Roman Empire and

India was more extensive than

previously thought and even

rivaled the legendary Silk Road,

archaeologists say.

"We talk today about globalism

as if it were the latest thing,

but trade was going on in

antiquity at a scale and scope

that is truly impressive," said

the co-director of the dig,

Willeke Wendrich of the

University of California at Los

Angeles.

Wendrich and Steven Sidebotham

of the University of Delaware

report their findings in the

July issue of the journal

Sahara. Historians have long

known that Egypt and India

traded by land and sea during

the Roman era, in part because

of texts detailing the

commercial exchange of luxury

goods, including fabrics, spices

and wine.

Now, archaeologists who have

spent the last nine years

excavating the town of Berenike

say they have recovered

artifacts that are the best

physical evidence yet of the

extent of sea trade between the

Roman Empire and India.

They say the evidence indicates

that trade between the Roman

Empire and India was as

extensive as that of the Silk

Road, the trade route that

stretched from Venice to Japan.

Silk, spices, perfume, glass and

other goods moved along the Silk

Road between about 100 B.C. and

the 15th century.

"The Silk Road gets a lot of

attention as a trade route, but

we've found a wealth of evidence

indicating that sea trade

between Egypt and India was also

important for transporting

exotic cargo, and it may have

even served as a link with the

Far East," Sidebotham said.

Among their finds at the site

near Egypt's border with Sudan

included more than 16 pounds (7

kilograms0 of black peppercorns,

the largest stash of the prized

Indian spice ever recovered from

a Roman archaeological site.

Bernike lies at what was the

southeastern extreme of the

Roman Empire and probably

functioned as a transfer port

for goods shipped through the

Red Sea. Trade activity at the

port peaked twice, in the first

century and again around 500,

before it ceased altogether,

possibly after a plague.

Ships would sail between

Berenike and India during the

summer, when monsoon winds were

strongest, Wendrich said. From

Berenike, camel caravans

probably carried the goods 240

miles (386 kilometers) west to

the Nile, where they were

shipped by boat to the

Mediterranean port of

Alexandria, she said. From

there, they could have moved by

ship through the rest of the

Roman world.

www.mikalina.com/images/silk_road.jpg

(Los Angeles AP Also cf.

Kodungallur by Prof. George

Menachery, 1987 & Roads to

India, Maggy Menachery, St.

Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia

of India, ed G Menachery, 1973.

www.indianchristianity.com BOOKS

page.

Refer the book Kodungallur

Cradle of Christianity in India,

by Prof. George Menachery (1987)

at www.indianchristianity.com.on

BOOKS page. Also article "Roads

to India" by Maggy G. Menachery,

in the St. Tomas Christian

Encyclopaedia of india, 1973,

Ed. Prof. George Menachery.

|

THE SEA-ROUTE TO INDIA & THE RED

SEA TRADE

|

|

As

Vasco da Gama forced his way up

the East African coast, he

sought a pilot who could guide

his ships to India. But da Gama

was not the most patient or

forgiving of Portuguese

explorers and his quick, violent

temper made the task more

difficult; a minor incident in

Mozambique prompted da Gama to

bombard the city. It would only

be at Kilwa that a suitable

pilot could be found. Ibn Majid,

the most distinguished Asian

navigator of his time, was

retained by the Portuguese

captain. Under Majid's expert

guidance, the Portuguese ships

quickly made their way to

western India. "On Friday, 18th

May," wrote da Gama in his

Journal, "after having seen no

land for twenty-three days, we

sighted lofty mountains, and

having all this time sailed

before the wind we could not

have made less than 600 leagues.

The land, when first sighted,

was at a distance of eight

leagues, and our lead reached

bottom at forty-five fathoms."

After finally landing in Calicut,

da Gama's journal records that

the Portuguese sailor was

greeted with the words "May the

devil take thee! What brought

you hither?" When asked what he

sought so far away from home, da

Gama replied that he came in

search of Christians and of

spices.

This was not, however, the

Orient that the European captain

thought he would encounter.

Instead of finding a single

opulent realm, da Gama found

innumerable states with a vast

and complex commercial network.

Perhaps more surprising was that

in the Indian Ocean ports that

it had taken the Portuguese

nearly a century to find by sea,

da Gama found merchants who for

centuries had been trading

European metals and gold bullion

for Indian and imported spices

through the Venetians. In

addition to European goods, da

Gama also saw items from North

Africa and Malaya, and gold and

ivory from East Africa. The

distances involved astounded da

Gama.

As an example of how vast these

trading routes were, we have

only to look at the trade in the

Indian Ocean, where the

prevailing monsoons determined

the course of trade. Between

November and April, the monsoons

blow from the north-east and

from May to October, the

monsoons blow from the

south-west. In southern Malay,

where the north-east winds of

the Indian Ocean meet the

south-west winds of the China

seas, Malacca emerged as the

"richest place in the world". In

Malacca, the Portuguese found

the business of the city was

conducted by all manner of

merchants and seamen. Merchants

gathered from the furthest

reaches of the known world,

Tunis and China, bringing with

them Chinese silks, Indian

textiles, East Indian spices,

and European goods that arrived

via Cairo and Aden. The

merchants were Christians, many

more were Hindu, but all managed

to co-exist peacefully in this

environment, and the Portuguese

soon discovered that most seamen

and traders in the Indian Ocean

and beyond were Muslims, a

forbidding development for da

Gama who when asked what had

brought him across such a great

distance replied "Christians and

spices".

In India, da Gama encountered

the same difficulties he had

when his ships were in Indian

Ocean ports. Without suitable

goods to trade, Portuguese

attempts to enter the lucrative

commerce of the region were

unsuccessful. Furthermore,

Portuguese arrogance and

disregard for local custom soon

eroded the initial goodwill

displayed by the Hindu raja. In

certain instances, the

Portuguese improperly worshiped

at Hindu shrines, and da Gama

kidnapped some of the local

inhabitants to serve as

interpreters for subsequent

voyages, all of which served to

antagonise the local population.

Perhaps more importantly, local

merchants, who learned of

Portuguese behaviour in Africa

and who were seeing it displayed

in their own country, had no

desire to see their livelihood

destroyed and refused to trade

with the Europeans.

Approximately half the fleet

with which da Gama departed

Lisbon two years before survived

to make the return voyage home.

As a feat of nautical endurance

and skill, da Gama's voyage was

a superb testament to the raw

maritime skills of the

Portuguese - nearly 300 days

were spent at sea. But it must

be remembered that the sea route

to India was found only with the

expert guidance of Ibn Majid who

knew how to properly use the

wind system of the Indian Ocean.

Da Gama was amply rewarded for

his services despite the fact

that he did not return with the

desired alliances, nor was he

able to secure any commercial

concessions. Still, while in

Calicut, the Portuguese captain

took into his service a Tunisian

Muslim and a Spanish Jew from

whom he learned some of the

intricacies of the Asian economy

and how it might be manipulated

to serve Portuguese interests.

Armed with this important

information, King Manuel I was

determined to establish a

monopoly on the spice trade of

the Indian Ocean by "cruel war

with fire and sword".

MARITIME TRADE

After Vasco da Gama reached

India in 1498, the Portuguese

Crown moved to secure the safety

of the sea route and sent da

Gama to accomplish this task.

During his voyage, da Gama

encountered stiff Muslim

opposition to Portuguese

attempts to enter the trade of

the Indian Ocean, and

consequently the Portuguese

captain believed he would have

to force his way into the

market. Fortunately for the

Portuguese, the empires of

Egypt, Persia and Vijayanagar

did not arm their vessels, if

they had ships at all. Malay

vessels, primarily known as

lanchara, were small, single

square-rigged vessels steered by

two oars mounted in the stern.

By and large, most Muslim

merchants had large ocean-faring

ships, complemented by smaller

coastal ships, but even these

were not outfitted to carry

artillery and no iron was used

in their hull construction.

Consequently, the merchants'

vessels were much more

susceptible to damage than were

the Portuguese ships and this

meant that the Portuguese were

able to gain control of the

Indian Ocean with relative ease.

Prior to the emergence of the

Portuguese, control of maritime

trade in the Indian Ocean was

established peacefully. Over the

centuries, a mutually beneficial

relationship developed between

Muslim traders and Hindu

merchants and the Portuguese

could offer little in the way of

goods or services to supplant

the established network.

Moreover, the Portuguese

believed that Venetian merchants

were monopolising trade of

European goods and preventing

them from gaining access to the

lucrative markets in the Indian

Ocean. The Portuguese quickly

surmised that they could only

change the status quo by

resorting to brute force.

Refer the book Kodungallur

Cradle of Christianity in India,

by Prof. George Menachery (1987)

at www.indianchristianity.com.on

BOOKS page. Also article "Roads

to India" by Maggy G. Menachery,

in the St. Tomas Christian

Encyclopaedia of india, 1973,

Ed. Prof. George Menachery. Also

the 15 books and 22 extracts

from books in The Indian Church

History Classics, Vol. I: The

Nazranies, 1998 ed.Prof. George

Menachery.

|

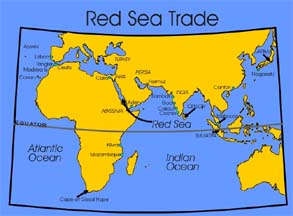

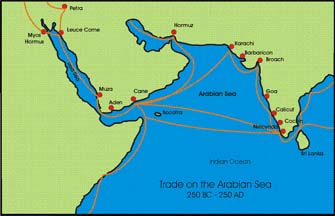

-

The Red Sea Trade Route

-

250 BC - 250 AD

|

|

During the period between 250 BC

and 250 AD, a maritime sea route

existed between Alexandra in

Northern Africa and China. As

trade took place along this

route, a number of kingdoms rose

to power, flush with finances

from trade. These kingdoms all

came into being around the same

time, and all waned around the

same time.

Trade on the Red Sea was in the

hands of merchants based out of

Alexandria. Nabataeans moved

trade from Southern Arabia to

their port of Leuce Come by

boat, and then overland to

Alexandria. "Arab" merchants

also brought Indian and Asian

goods to the ports on the

Egyptian side of the Red Sea.

For a time it may have been

Indian ships that brought the

good to Southern Arabia, as

Diodorus tells us of the

'prosperous islands near

Eudaemon Arabia which were

visited by sailors from every

port of the world, and

especially from Potana, the city

which Alexander the Great

founded on the Indus river.' (Diodorus.

3.47.9.) |

|

|

Another description of this

situation is found in a text

known as 'The Periplus of the

Erythraean Sea' by an unknown

author. Many have assumed he was

a Greek living in Alexandria,

but he may have just as well

have been an Arab merchant with

a Greek name living in

Alexandria. In it we read that 'Eudaemon

Arabia (Aden) was once a

fully-fledged city, when vessels

from India did not go to Egypt

and those of Egypt did not dare

sail to places further on, but

came only this far.' (L. Casson,

ed. The Periplus Maris Erythraei

(Princeton 1989) 26., lines

26-32) Any attempts by

Alexandrian ships to sail beyond

Aden were strongly discouraged;

if they did sail, it was by

laboriously hugging the coasts

and in the words of Periplus,

'sailing round the bays'. |

|

|

This was the situation until

Roman financiers entered the

Alexandrian money market towards

the middle of the 2nd century

BC. The ensuing rise of demand

for oriental and southern goods

in the Mediterranean markets

whetted the appetite of Arab

merchants based in Alexandria to

increase their share in the

north-south trade. They realized

that they needed to sail

directly across the Indian Ocean

to the rich Indian market and

bring good back to Egypt,

without the involvement of

Indian merchants. Ptolemy VIII,

friend of Rome, as was his wife

after him, demonstrated personal

interest and involvement in the

project which indicated the

great hopes all parties in

Alexandria attached to the

success of the venture. While it

is not known who made the first

direct voyage to India, very

soon a new important office was

created for the first time in

the Egyptian administration. It

was know as the 'commander of

the Red and Indian Seas,' and

came into being under Ptolemy

XII, nicknamed Auletes (80-51

BC). (Sammelbuch, 8036, Coptos

(variously dated 110/109 BC or

74/3 BC; and no. 2264 (78 BC);

Inscriptions Philae, 52 (62 BC)

The creation of such an office

implies that the perhaps at this

time there was a marked increase

in the regular commercial

transactions with India.

It is also perhaps not entirely

irrelevant that in 55 BC, the

Senate decided to send Gabinius

at the head of a Roman army to

restore Auletes (Ptolemy XII) to

his throne and to remain in

Alexandria for the protection of

the king against possible future

revolts. (Caesar, BC. 3. 110).

We can easily detect behind this

drastic step, considerable Roman

assets at risk in the case of

sudden undesirable internal

changes in Alexandria.

This should warn us against

accepting at face value Strabo's

often quoted remark that it was

only under 'the diligent Roman

administration that Egypt's

commerce with India and

Troglodyte was increased to so

great an extent. In earlier

times, not so many as twenty

vessels would have dared to

traverse the Red Sea far enough

to get a peep outside the

straits (Bab-el-Mandab), but at

the present time, even large

fleets are dispatched as far as

India and the extremities of

Aethiopia, from which the most

valuable cargoes are brought to

Egypt and thence sent forth

again to other regions.' (Strabo,

17.1.13.) This is clearly an

overstatement, intended as a

compliment to the new Roman

administration, considering that

Aelius Gallus, the prefect of

Egypt, was Strabo's personal

friend at whose house he stayed

as a guest for five years (25-20

BC). Strabo's statement stands

in sharp contrast to the earlier

data of the above mentioned

inscriptions and to the more

matter-of-fact statement of the

later author of the Periplus (c.

40 AD), who rightly perceived

that the great change in the

modes of navigation and the vast

expansion of trade were the

direct result of the discovery

of the Monsoon winds, at least

half a century before Augustus

conquered Egypt. Strabo himself

witnessed the flourishing state

of Alexandria only five years

after the Roman conquest, and

very shrewdly observed the

active trade that went through

its several harbors. He says,

'Among the happy advantages of

the city, the greatest is the

fact that this is the only place

in all Egypt which is by nature

well situated with reference to

both things, both to commerce by

sea, on account of the good

harbors, and to commerce by

land, because the river easily

conveys and brings together

everything into a place so

situated, the greatest emporium

in the inhabited world.'

Soon after the annexation of Egypt, Emperor Augustus (Rome 63 BC - Nole 14

AD) in 26 BC commissioned his

prefect in Egypt, Aelius Gallus,

to invade southern Arabia by

land. (Strabo, 16.4.23-4.) This

land onslaught caused

considerable damage to the

Sabaeans as far as Marib, and

allowed the Himyarites, close

friends of the Nabataeans to

soon take control of most of

Southern Arabia. Some writers

have thought that around AD 1

Augustus launched another

devastating attack - this time

by sea - which resulted, in the

words of Periplus,'in sacking

Eudaemon Arabia' which declined

into, 'a mere village after

having been a fully fledged city

(polis)'. (Periplus, 26; Pliny,

H.N. 6.32, 160 & 12.30,55; Also

cf. H. MacAdam, 'Strabo, Pliny

and Ptolemy of Alexandria', in:

Arabie Pre-Islamique (Strasbourg

1989) 289-320.) Now that

Eudaemon Arabia (Aden) was out

of action, merchants from

Alexandria experienced

unrivalled dominance of the sea

route to India.

|

|

Pattanam dated to 1st millennium

BCE

The radiocarbon analysis at the

Institute of Physics,

Bhubaneswar, has put the

antiquity of Pattanam (Kerala,

India) to the first millennium

BCE. What is more, the studies

suggest that the canoe found in

a water-logged trench at

Pattanam canoe could be the

earliest known canoe in India.

The five samples that were

analysed include charcoal

samples and parts of the wooden

canoe and bollards recovered

from trenches. The mean calendar

dates of these five samples

place the antiquity of ancient

maritime activity of Pattanam at

about 500 BCE. The artefacts

have revealed that the site had

links with the Mediterranean,

Red Sea, Arabian Sea and South

China Sea rims since the Early

Historic Period of South India. |

|

|

"Pattanam

is the first habitation site of

the Iron Age ever unearthed in

Kerala. Since previous enquiries

were confined to megalithic

burials, no firm dates were

available for the Iron Age,

except a few like Mangadu (circa

1000 BCE) and unnoni," said P.J.

Cherian, project director of

Pattanam excavations. The

radiocarbon dates from Pattanam

is therefore expected to help in

understanding the Iron Age

chronology of Kerala.

"The indigenous people seems to

have settled on the site during

the Iron Age when this area was

covered by beach sand. The

occupation has been sparse and

the sand deposit has mostly

black-and-red ware and other

typical `megalithic' pottery,"

added P.J. Cherian.

The Archaeological Survey of

India has granted licence to

Project Director P.J. Cherian

for a second consecutive season

and the work is scheduled to

begin in February 2008. Besides

the excavation activities at

Pattanam, the licences are for

archaeological exploration

within 50 km around Kodungallur

and underwater explorations in

the water-bodies within 20 km

radius. |

| |

|

|